Locking knee physiotherapy

By Nigel Chua‘Locking knee’ is a fairly common complaint by athletes who have twisted their knees in sports like basketball, netball, soccer or badminton. This experience of ‘knee locking’ is an indication of a possible meniscus tear.

The knee meniscus, which is a moon-crescent shaped cartilage located between the knee, acts as a shock cushion to absorb the impact between the leg and thigh bone.

Our meniscus is better at the handling loads/forces from a vertical motion (up and down) due to the way it's shaped.

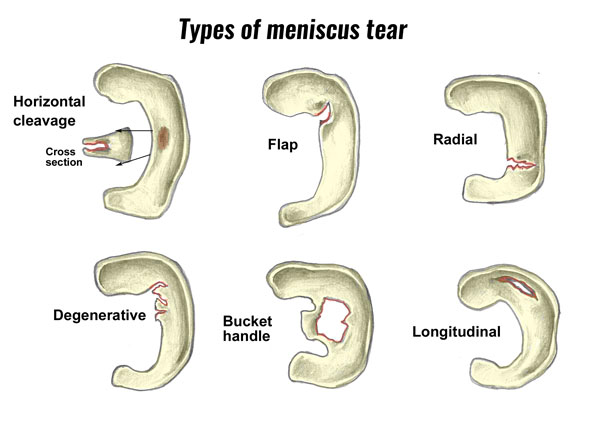

Unfortunately, our meniscus is susceptible to a twisting injury especially when it's both compressed and twisted, which can cause a tear in the meniscus. The "locking" happens when the torn part of the meniscus blocks the movement of the knee.

Normally immediately after meniscus injury, there will be immediate swelling and a sharp pain in the knee. But sometimes there are delays in the onset of swelling, or sometimes there is no swelling at all (depending on the severity and location of the meniscal partial tear).

Please do remember how you injured you knee as it will help your doctor or knee physiotherapist in diagnosing and treating this problem.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS FOR MENISCAL INJURY

Differential diagnosis is necessary to exclude injuries that may cause the same symptoms as MCL injury of the knee.

These injuries are:

- Medial meniscal tear/injury

- Anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) tear

- Tibial plateau fracture

- Femur injury or fracture

- Patellar subluxation/dislocation

- Medial knee contusion

- Pediatric distal femoral fracture

- Damage to the posteromedial corner structures.

A physical examination will help to ensure a correct diagnosis. A medial meniscal tear can be mistaken for an MCL sprain, because the tear causes joint tenderness like the sprain. With a valgus laxity examination, a medial meniscal tear can be differentiated from a grade 2 or 3 MCL sprain.

The presence of an opening on the joint line means the medial meniscus is torn. A grade 1 MCL is more difficult to differentiate from a medial meniscal tear.

The differentiation can be made through an MRI or by observing the patient during several weeks. In case of an MCL sprain, tenderness usually resolves, whereas with a meniscal injury it persists.

When there is tenderness, but no abnormal valgus laxity, it could be a case of medial knee contusion. If the tenderness is situated near the adductor tubercle or medial retinaculum adjacent to the patella, the cause is more likely to be patellar dislocation or subluxation.

Patellar instability can be differentiated from an MCL sprain with the patellar apprehension test. A positive result means there is patellar instability.

If the patient is a child, a gentle stress-testing radiograph can determine if they have a distal femoral fracture instead of an MCL sprain.

PHYSIOTHERAPY MENISCAL MANAGEMENT

The treatment of a medial collateral ligament injury rarely requires a surgical intervention. The medial collateral ligament appears to have a fairly robust potential for healing.

In cases where instability exists after non-operative treatment, or instances of persistent instability after ACL and/or PCL reconstruction, the MCL tear may be addressed through surgical repair or reconstruction.

The most isolated MCL injuries are successfully treated non-operatively with bracing or immobilization. Some simple treatment steps, together with rehabilitation, will allow patients to return to their previous level of activity.

Most treatment protocols focus on early range of motion, reducing swelling, protected weight bearing, progression toward strengthening and stability exercises. The general goal is to have an athlete or patient return to full activities.

The overall rehabilitation principles are:

- To control edema

- To initiate M. Quadriceps activation in the initial hours to days after injury

- To work to restore as early as possible the range of motion of the knee.

We can divide a medial knee injury in three grades.

Grade 1

The treatment for isolated grade 1 injuries is mainly non-operative.

During the first 48 hours, ice, compression and elevation should be used as much as possible. In general, incomplete tears of the MCL are treated with temporary immobilization and the use of crutches for pain control.

Isometric, isotonic and eventually isokinetic progressive resistive exercises are begun within a few days of the subsidence of pain and swelling. Weight-bearing is encouraged, the rate being dictated by the level of pain.

Grade 2/3

For a grade 2/3 injury, it is important that the ends of the ligament are protected and left to heal without continually being disrupted. One should avoid applying significant stresses to the healing structures until three to four weeks after the injury to ensure that the injury can heal properly.

The treatment for grade 3 injuries depends on whether the injury is isolated or combined with other ligamentous injuries.

For a grade 3 medial knee injury combined with an another injury, for example an ACL tear, the general protocol is the rehabilitation of the medial knee injury first so it can be allowed to heal according to the guidelines for an isolated medial knee injury.

When there is good clinical and/or objective evidence of healing of the medial knee injury, mostly 5 to 7 weeks after the injury, the reconstruction of the ACL can begin.

PHYSIOTHERAPY AND REHAB

Rehabilitation for non-operative treatment can be split into four phases:

Phase One: From 1-2 weeks

Phase one consists of controlling the swelling of the knee by applying ice (cold therapy) for 15 minutes every two hours, for the first two days. For the rest of the week, the frequency can be reduced to three times a day. Use ice as tolerated and as needed based on symptoms.

In the beginning the patient needs to use crutches. Early weight bearing is encouraged because patients can progressively reduce their dependence on crutches. Afterwards, progress to one crutch and let the patient stop using the crutches only when normal gait is possible.

Another aim of this phase is trying to maintain the ability to straighten and bend the knee from 0° to 90° knee flexion. For achieving the range of motion of the knee, it is important to emphasize full extension and progress flexion as tolerated.

Pain free stretches for the hamstrings, quads, groin and calf muscles (in particular) are suggested.

Lastly, there are therapeutic exercises. The patient may begin with static strengthening exercises as soon as pain allows it.

For example

- quadriceps sets

- straight leg raises

- range-of-motion exercises

- sitting hip flexion

- sidelying hip abduction

- standing hip extension

- standing

- hamstring curls.

As soon as patients can tolerate it, they are encouraged to ride a stationary bike to improve the range of motion of the knee. This will ensure accelerated healing.

The amount of time and effort on the stationary bike is increased as tolerated. Every patient is different and not all patients will do the same exercises.

There are no limits on upper extremity workouts that do not affect the injured knee. It’s important that the patient rests from all painful activities (use crutches if necessary), and that the MCL is well protected(by wearing a stabilized knee brace.

Phase Two: From Week 3

The aims for the range of motion are the same as in phase one.

Progress to 20 minutes of biking, and also increase the resistance as tolerated by the patient. Biking will ensure healing, rebuild strength and maintain the aerobic conditioning.

The physiotherapist can give other exercises like

- hamstring curls

- leg presses (double-leg)

- step ups.

As a precaution, the patient may be examined by a physician every three weeks to verify the healing of the ligament.

Phase Three: From Week 5

The major goal for this phase is full weight-bearing on the injured knee. Discontinue the use of a brace once ambulating with full weight bearing is possible, and there is no gait deviation. The range of motion must be fully achieved and symmetrical with the non-injured knee.

The therapeutic exercises are the same as in phase two.

We continue with cold therapy and compression to eliminate swelling. In this phase you can commence with balance and proprioceptive activities.

To maintain aerobic fitness, the patient can use the stepper, or (if possible) may begin to swim. As a precaution, the patient may be examined by a physician every five to six weeks, and undergo stress radiography when needed.

Phase Four: From Week 6

Discontinue wearing the brace while walking.

Athletics can wear the brace for competition for at least three months. Cold therapy still needs to be applied. The aim of the therapeutic exercises is more focused on sport-specific or daily movements.

The intensity of the strengthening exercises needs to be increased, and instead of double leg exercises, we change these to single leg exercises. The patient may start running again at a comfortable pace (make sure they don't make sudden changes of direction).

As a precaution, it is best to return to competition once full motion and strength is returned, and when the patient passes a sport functional test. Every patient is different so the application of these principles should be guided by the overall rehabilitation principles.

Do not hesitate to know more about Phoenix Rehab's physiotherapy for knee pain if you encounter such knee problems.

Browse other articles by category

Physiotherapy for Knee Pain Physiotherapy For Slipped Disc Physiotherapy for Neck Pain PHYSIOTHERAPY

PHYSIOTHERAPY

Hand Therapy

Hand Therapy

Alternative

Alternative

Massage

Massage

Traditional Chinese Medicine Treatment

Traditional Chinese Medicine Treatment

Rehab

Rehab

Physiotherapy For Lower Back Pain

Physiotherapy For Shoulder Pain

Orthopedic Doctors, Insurance & Healthcare

Physiotherapy For Upper Back Pain

Frozen Shoulder

Physiotherapy for Back Pain

Physiotherapy For Lower Back Pain

Physiotherapy For Shoulder Pain

Orthopedic Doctors, Insurance & Healthcare

Physiotherapy For Upper Back Pain

Frozen Shoulder

Physiotherapy for Back Pain

Whatsapp us now

Whatsapp us now