Treatment and Prevention for the Most Common Diving Injuries

By Yuna ZhuangDiving challenges both the body and mind in ways few other sports do. Beneath the surface or mid-air, divers face a unique mix of physics, physiology, and precision. However, along with the thrill comes real risk. The range of diving-related injuries is wide, from pressure-induced injuries to overuse strains, and the consequences can be serious if ignored. Knowing what can go wrong is the first step to making sure it doesn’t.

In this article, we'll explore the most common diving injuries, how they’re treated, and what divers can do to prevent them. We'll also discover how treatments like physiotherapy can help in both the preparation and recovery stages.

Scuba Diving Injuries

Diving is a physically demanding sport with inherent risks, especially when it involves underwater exploration with breathing apparatus. Scuba diving injuries differ from competitive diving due to the environment, equipment, and physiological challenges. Most scuba diving injuries are the result of pressure changes, absorption of breathing gases like nitrogen and oxygen, environmental encounters, or overexertion in a foreign and unpredictable setting.

Injuries frequently occur during the ascent and descent phases of a dive, when pressure is rapidly changing and the body must adapt accordingly. Others are linked to factors like temperature extremes, poor buoyancy control, fatigue, or panic. Divers also face dangers from marine life, equipment malfunction, or medical conditions exacerbated by immersion.

We'll break down the specific injuries and their mechanisms below.

Animal Bites and Stings

While many marine species are passive, scuba divers occasionally come into painful contact with jellyfish, sea urchins, stingrays, or lionfish. These stings and bites are typically defensive in nature, triggered when a diver unknowingly invades the animal's territory or brushes against it. Some sea creatures have venomous spines or stingers that can cause severe pain, allergic reactions, or, in rare cases, systemic illness.

When dealing with this situation, here are some things that you can do:

- Clean the affected area thoroughly and remove any embedded spines or tentacles carefully.

- Soak the wound in hot water (not scalding). This can neutralise venom and alleviate discomfort.

- Take over-the-counter pain relief and antihistamines to help with inflammation, but medical attention is essential if symptoms worsen.

- Anaphylaxis and secondary infections are risks that shouldn’t be taken lightly.

Prevention involves keeping a respectful distance from marine life and avoiding contact with the ocean floor. Protective wetsuits, gloves, and awareness of the surroundings greatly reduce the likelihood of such encounters.

Arterial Gas Embolism (AGE)

AGE is one of the most dangerous diving disorders. It occurs when expanding air during a rapid ascent causes alveolar rupture in the lungs, allowing gas bubbles to enter the bloodstream. These bubbles may travel to vital organs, such as the brain or heart, blocking blood flow and causing immediate symptoms.

Signs include:

- Sudden chest pain

- Difficulty breathing

- Confusion

- Dizziness

- Paralysis

- Loss of consciousness

This is a rare but life-threatening emergency requiring immediate 100% oxygen administration and evacuation to a hyperbaric chamber. To prevent this, you must never hold your breath while ascending, no matter how shallow the dive. Divers should ascend slowly and continuously, following dive computer instructions or dive tables. Pre-dive briefings should always stress the importance of controlled ascent and the risks associated with panic or poor training.

Barotrauma

Barotrauma occurs when divers fail to equalise pressure in air-filled cavities such as the middle ear, sinuses, lungs, or even the gastrointestinal tract. The rapid change in ambient pressure causes tissues to stretch, rupture, or bleed, with ear barotrauma and sinus barotrauma being most common.

Symptoms include:

- Severe ear pain

- Dizziness

- Nosebleeds

- Muffled hearing

In severe cases, ruptured eardrums or inner ear damage may result, leading to hearing loss or permanent balance issues. Lung barotrauma is more serious, potentially leading to arterial gas embolism or pulmonary oedema.

Divers should always descend slowly, equalise early and often, and avoid diving with nasal congestion. Decongestants may help before a dive, but they must be used with caution. If barotrauma is suspected, diving should be stopped immediately to prevent further injury, and medical attention should be sought.

Cuts and Bruises

Though they may seem minor, cuts and bruises can escalate into more serious issues underwater. These injuries typically result from accidental contact with coral reefs, sharp rocks, or equipment during entry and exit. Coral wounds are particularly prone to infection due to biological contaminants.

Here's a standard protocol for these injuries:

- The affected area should be cleaned thoroughly with clean, fresh water, followed by antiseptic application and bandaging.

- Divers should carry a waterproof first aid kit in the boat or at the dive site.

- If a wound becomes red, swollen, or painful, medical attention is warranted.

Prevention is mostly behavioural and equipment-based: careful buoyancy control, situational awareness, and the use of protective wetsuits or gloves can significantly reduce the risk of contact-related injuries. Proper dive planning and entry techniques also help prevent impact-related bruises.

Decompression Sickness (DCS)

Decompression sickness, or "the bends", results from dissolved nitrogen forming bubbles in the blood and tissues when a diver ascends too quickly. These bubbles can cause joint pain, neurological symptoms, or shortness of breath, depending on their location and size.

Early signs include:

- Fatigue

- Skin rash

- Dizziness

- Pain in the joints and muscles

Severe cases may lead to paralysis or death if untreated. Immediate administration of 100% oxygen, hydration, and urgent transport to a hyperbaric chamber are essential.

To avoid DCS, divers must:

- Ascend slowly.

- Observe no-decompression limits.

- Make safety stops.

Dive computers are effective tools for monitoring ascent rates and nitrogen absorption. Staying well-hydrated and avoiding strenuous activity post-dive also reduces the risk of bubble formation in body tissues.

Drowning

Although relatively rare among experienced scuba divers, drowning remains a leading cause of scuba diving accidents. It is typically caused by panic, loss of buoyancy, entrapment, or equipment failure. A diver who loses consciousness or cannot reach the surface may inhale water, leading to respiratory failure.

Prompt rescue and first aid are critical. Administer rescue breaths as soon as the diver is brought to the surface, followed by CPR if necessary. Professional medical evaluation is always required.

Preventing drowning involves proper training, buddy systems, regular equipment checks, and calm underwater behaviour. Divers must be proficient in emergency procedures, including mask clearing and air-sharing techniques.

Heat Stroke and Sunburn

Surface intervals on sunny dive boats or beaches can expose divers to extreme heat. Without proper sun protection, heat stroke and sunburn can develop quickly, leading to dehydration, nausea, confusion, and in serious cases, collapse or skin damage.

Cooling the body with water or shade, rehydrating with fluids, and applying cold compresses are immediate responses. Severe cases should be treated in a medical facility.

Divers should wear UV-protective clothing, apply high-SPF sunscreen between dives, and stay shaded during surface breaks. Hydration before and after the dive is equally important to avoid heat-related illness.

Hypothermia

Even in tropical waters, long dives can cause hypothermia due to the body’s heat loss underwater. Cold conditions reduce core body temperature gradually, affecting performance, awareness, and breathing.

Symptoms include shivering, slurred speech, poor coordination, and lethargy. If suspected, the diver should be removed from the water, dried, and slowly warmed with blankets and warm (not hot) fluids.

Wearing a properly rated wetsuit or drysuit is an effective preventive measure. Dive durations should be adjusted according to temperature, and signs of cold stress should never be ignored.

Irregular Heartbeat

Cold shock, stress, or CO2 buildup can trigger arrhythmias or irregular heartbeats, especially during breath-hold diving or immersion in cold water. For individuals with pre-existing conditions, this may lead to fainting or even cardiac arrest.

Any episode of chest discomfort, palpitations, or loss of consciousness during a dive requires immediate medical evaluation. Divers with known heart issues must consult a physician before diving.

Warming up before water entry and avoiding overexertion or hyperventilation helps minimise the risk. Proper breathing and pacing during dives are crucial for managing physiological stress.

Oxygen Toxicity

Oxygen toxicity arises from breathing high partial pressures of oxygen, typically during deep or technical dives using enriched air or rebreathers. It can affect the central nervous system, leading to twitching, tunnel vision, or seizures underwater—an extremely dangerous scenario.

If symptoms occur, the diver should surface immediately in a controlled manner and breathe normal air. Medical assessment is important after any suspected episode.

To prevent this, divers should use dive planning software or tables to monitor oxygen exposure. Adhering to MODs (Maximum Operating Depths) and staying within gas mix limits is critical for technical dives.

Pulmonary Oedema From Immersion

Immersion pulmonary oedema can occur even in healthy divers. It involves the accumulation of fluid in the lungs during exertion in cold water, likely due to blood pressure shifts and changes in lung circulation.

Symptoms include:

- Coughing

- Shortness of breath

- Chest tightness, often during or shortly after a dive

If suspected, the diver should immediately exit the water and receive supplemental oxygen. Hospital evaluation is necessary. Prevention includes avoiding overexertion, especially in cold conditions. Divers should pace themselves, stay warm, and monitor for symptoms if they’ve had previous episodes.

Motion Sickness

Motion sickness can affect divers before or after a dive, especially on boats in choppy seas. Nausea, dizziness, and vomiting can make diving unpleasant and dangerous if they lead to dehydration or disorientation underwater.

Treat with anti-nausea medication, fluids, and rest. Ginger supplements or acupressure bands may also help some divers. Prevent motion sickness by taking medication 30–60 minutes before boarding. Before the dive, keep yourself hydrated and avoid heavy meals to reduce the risk of discomfort.

Nitrogen Narcosis

Nitrogen narcosis is a reversible, pressure-induced alteration of consciousness occurring at depths usually beyond 30 metres. As nitrogen concentration in the central nervous system increases, divers may feel euphoria, poor judgment, or disorientation, commonly likened to alcohol intoxication.

Symptoms disappear as the diver ascends to shallower depths. However, while under the influence, poor decisions can lead to other diving injuries or scuba diving accidents.

The key to prevention is to limit dive depth according to experience and comfort level. Avoid deep dives when fatigued or stressed, and always dive with a buddy who can recognise behavioural changes.

Scuba Diving Injuries – Treatment

Treating scuba diving injuries starts with recognising symptoms early and responding decisively. Because many diving-related conditions, like arterial gas embolism (AGE) or decompression sickness (DCS), can worsen rapidly, the first few minutes are crucial:

- Immediate oxygen treatment is often the recommended first-line response, as it helps reduce bubble size in the blood and supports oxygen-starved tissues.

- In moderate to severe cases, divers must be transferred as soon as possible to a hyperbaric facility for recompression therapy.

For other common diving injuries like barotrauma, hypothermia, or pulmonary oedema from immersion, the following supportive care may be enough:

- Warming the body

- Rest

- Hydration

- Decongestants

In these instances, medical evaluation is still advised. Minor injuries, including cuts, bruises, or sunburn, can be treated with basic first aid: clean the area, apply an antiseptic, and protect the skin. However, signs of infection, persistent pain, or systemic symptoms should not be ignored.

Dive operators and buddy teams must always carry a comprehensive first aid kit, know how to administer oxygen, and have an action plan for emergencies. Immediate contact with emergency services or the Divers Alert Network (DAN) can be lifesaving, especially in remote dive sites.

Scuba Diving Injuries – Prevention

Most scuba diving injuries are avoidable with the right mindset, preparation, and in-water discipline. Prevention hinges on anticipating what might go wrong and making sure you’re physically, mentally, and technically prepared to handle it. This includes understanding the unique challenges of every dive (depth, temperature, environment) and respecting personal limits and established dive protocols.

Beyond individual awareness, prevention also relies on proper gear maintenance, good communication with dive buddies, and having contingency plans in place. Divers should never underestimate how quickly a small oversight can escalate into a serious problem.

Below are practical steps that help reduce the risk of injury:

Proper Preparation

- Be medically fit for diving. Underlying health issues like asthma, heart conditions, or anxiety can increase the risk of diving injuries.

- Get certified and regularly update your skills. Refresher courses ensure you stay sharp and confident, especially if it’s been a while since your last dive.

- Plan your dive and dive your plan. Know your entry/exit points, maximum depth, bottom time, and emergency protocol.

- Check all gear before each dive. Faulty regulators, leaky masks, or ill-fitting wetsuits can compromise your safety underwater.

Precautions

- Equalise often during descent and ascent. This prevents ear barotrauma and sinus barotrauma, which are among the most common diving injuries.

- Ascend slowly to avoid decompression illness. Follow no-decompression limits and never skip your safety stop.

- Use dive computers or tables to monitor pressure and time. These tools help track nitrogen absorption and alert you to the effects of rapid ascents.

- Know the signs of oxygen toxicity, nitrogen narcosis, and barotrauma. Recognising symptoms early can mean the difference between a manageable incident and a full-blown emergency.

When prevention becomes part of your routine (not just a checklist!), you dramatically lower your chances of experiencing scuba diving accidents and improve your overall confidence and enjoyment in the water.

Competitive Diving Injuries

Competitive diving places immense stress on the body, particularly on joints, tendons, and muscles. Unlike scuba diving accidents, which are often environmental or pressure-related, competitive diving injuries are largely mechanical and repetitive.

Athletes perform high-impact water entries, acrobatic twists, and rapid directional changes, all of which demand explosive strength, flexibility, and control. The strain is especially acute during take-offs from the board and landings in water, where improper form or fatigue can increase the risk of injury.

Most injuries in this sport are overuse-related or due to incorrect technique. Divers, especially those training intensely or transitioning to higher platforms, are more likely to experience shoulder dislocations, back pain, or knee stress. Even a slight misalignment during entry can lead to long-term issues without proper conditioning and form. Early detection, adequate recovery time, and a balanced training regimen are key to keeping divers in peak form and avoiding chronic diving-related injuries.

Dislocated Shoulder

A shoulder dislocation occurs when the upper arm bone (humerus) pops out of its socket in the shoulder blade. In diving, this usually happens during take-off or high-impact entry when the arm is forced backwards or overhead with sudden force. Novice divers are prone to this injury due to weaker stabilising muscles or poor technique, though even elite athletes are at risk during complex routines. Once dislocated, the shoulder becomes vulnerable to future instability or labral tears.

Symptoms include intense pain, visible shoulder deformity, and limited mobility. Immediate treatment involves reducing the joint (performed only by a medical professional), immobilisation, and rest. Recovery requires strengthening of the rotator cuff and scapular muscles to restore joint stability. Preventing re-injury involves refining technique, focusing on controlled entries, and building shoulder resilience through sport-specific training.

Rotator Cuff Injury

The rotator cuff comprises four small but critical muscles that stabilise the shoulder joint. Repetitive overhead motions—common in competitive diving—can lead to inflammation, strain, or tearing of these muscles. Aggressive training schedules, poor form, or muscle fatigue contribute to the breakdown of rotator cuff integrity.

Early signs include a dull ache in the shoulder, weakness when lifting the arm, and difficulty sleeping on the affected side. Divers may also notice reduced control during entry or take-off. Mild cases respond to rest, ice, anti-inflammatory treatment, and physiotherapy, but chronic tears may require imaging or even surgical repair. A prevention strategy should include regular shoulder mobility checks, dynamic warm-ups, and rotator cuff strengthening exercises to manage the demands of diving.

SLAP Injury

A SLAP (Superior Labrum Anterior to Posterior) tear involves damage to the cartilage ring that stabilises the shoulder socket. In diving, this often results from forceful overhead movements during take-off, twisting mid-air, or hard water impact with an extended arm. SLAP injuries can also stem from sudden stops or overreaching during a dive gone wrong.

The injury typically presents as deep, poorly localised shoulder pain, often accompanied by a catching or popping sensation. Athletes may experience reduced range of motion and power, especially during arm rotation or pushing movements. Diagnosis requires clinical examination and possibly an MRI. Conservative management includes physiotherapy and shoulder strengthening; however, severe or unresponsive cases may require arthroscopic surgery. Technique adjustments and limiting overuse are crucial in reducing recurrence.

Back Pain

Lower back pain is one of the most common overuse complaints in competitive divers. The cause is often repetitive spinal extension, flexion, and rotation during take-offs, tucks, twists, and entries. These movements put stress on the lumbar vertebrae, intervertebral discs, and surrounding musculature, particularly when core strength or spinal alignment is suboptimal.

Tight hamstrings and hip flexors can also contribute by altering pelvic tilt and load distribution during motion. Divers may report aching or sharp pain, stiffness, or decreased range of motion. Early intervention with stretching, strengthening, and posture correction is key. Chronic or acute pain should prompt medical evaluation to rule out disc herniation or stress fractures. A prevention plan includes regular core stability work, dynamic stretching, and technique refinement to avoid hyperextension under load.

Wrist Joint Injuries

Wrist injuries in diving typically occur during entry, especially when the diver over-rotates or misaligns in a hand-first landing. The wrists absorb a sudden, concentrated impact from the water’s surface, which can result in ligament sprains, cartilage damage, or even bone bruising.

Symptoms include wrist pain, swelling, and reduced grip strength or flexibility. Some divers may develop chronic issues like tendonitis from repeated microtrauma. Mild injuries respond well to ice, rest, and wrist bracing. Persistent or severe symptoms may need imaging to assess for ligament tears or instability. Strengthening forearm muscles, learning proper entry positioning, and using pre-hab exercises can reduce stress on the joint and lower injury risk.

Jumper’s Knee

Jumper’s knee, or patellar tendinopathy, is a repetitive strain injury affecting the tendon that connects the kneecap to the shinbone. It’s common in sports with explosive jumping, and divers are no exception, particularly those training frequently from the springboard. Constant take-offs place the patellar tendon under high load, leading to microscopic tears and tendon degeneration over time.

Symptoms include pain and tenderness just below the kneecap, which worsens during jumping or squatting. If untreated, it may limit training or lead to chronic knee dysfunction. Treatment typically involves activity modification, eccentric strengthening exercises, and physical therapy. Ice and anti-inflammatories help in the early stages. Preventive measures focus on strengthening the quadriceps and glutes, improving jump mechanics, and balancing training with adequate recovery.

Knee Cap Injuries and Patellofemoral Pain

Patellofemoral pain syndrome is characterised by discomfort around or behind the kneecap, often caused by poor alignment, muscle imbalances, or hard water entry. This condition is frequently seen in divers who have weak hip stabilisers or uneven lower limb mechanics, especially during the transition from board to water.

Pain typically presents during kneeling, stair climbing, or after prolonged sitting, and may be accompanied by clicking or grinding sensations. Divers may also notice a sense of instability or catching in the joint. Treatment involves strengthening the quadriceps, hamstrings, and hip muscles, along with manual therapy to improve patellar tracking. Taping or bracing may help during training. Ensuring correct technique and landing alignment goes a long way in preventing aggravation.

Medial Tibial Stress

Known more widely as shin splints, medial tibial stress syndrome is an overuse injury affecting the lower leg, especially in sports involving frequent take-offs and landings. Divers are susceptible due to repeated loading on hard pool decks or platforms before water entry.

Pain begins along the inner edge of the tibia and may start as a dull ache, progressing to sharper pain with continued use. Left unmanaged, it can develop into a stress fracture. Rest, ice, and anti-inflammatories provide early relief, while longer-term management includes load modification, improved footwear, and strengthening of lower limb muscles. Preventive focus should be on technique during take-offs, proper landing mechanics, and cross-training to reduce repetitive load.

Sprained Ankle

Ankle sprains are typically caused by poor take-off posture, awkward landings, or slipping on wet platforms. A sprain happens when ligaments around the ankle joint stretch or tear due to sudden twisting or rolling of the foot.

Symptoms include pain, swelling, bruising, and instability, which can limit a diver’s ability to push off the board or maintain control during entry. Mild sprains recover with RICE and gradual rehab, but severe tears may require immobilisation or physiotherapy. In these cases, an appropriate ankle sprain treatment plan is essential to restore strength and prevent reccurence.

Repeated ankle sprains may lead to chronic instability if not managed properly. Prevention strategies include balance training, proprioception drills, and strengthening the muscles around the ankle.

Achilles Tendinopathy

The Achilles tendon is heavily loaded during diving due to repeated jumping and pushing off from boards. Over time, this can lead to tendinopathy—a degenerative condition resulting from overuse and insufficient recovery.

Symptoms include stiffness and pain near the back of the heel, especially during the first steps after rest. The tendon may be tender to touch and slightly thickened. Early management includes rest, ice, heel lifts, and eccentric loading exercises to restore tendon strength. Divers should also examine their training load and incorporate calf and ankle mobility work. Preventive care includes proper warm-ups, maintaining ankle flexibility, and avoiding sudden increases in intensity

Competitive Diving Injuries – Treatment

Managing injuries in competitive diving requires a proactive and structured approach. While many diving-related injuries are minor and self-limiting, others can become chronic or recurrent if not treated properly. Soft-tissue injuries, overuse syndromes, and joint strain are all common due to the sport’s physical demands. Early treatment helps prevent long-term complications and ensures athletes can return to training safely and efficiently.

The key is to treat not just the symptoms but the underlying cause. Diving coaches, athletes, and physiotherapists should work together to develop a personalised recovery plan tailored to the injury and the diver’s needs. Here’s a breakdown of the core treatment strategies.

RICE

The RICE method (Rest, Ice, Compression, and Elevation) is the immediate first aid response for soft-tissue injuries such as sprains, strains, and bruises.

- Rest allows tissues to heal without further stress.

- Icing within the first 48 hours reduces inflammation and pain.

- Compression (with wraps or sleeves) helps minimise swelling.

- Elevation promotes fluid drainage and circulation.

This approach is effective in the early phase of recovery and should be followed by gradual reintroduction of movement and strength exercises.

Taping, Bracing, Orthotics

Supportive devices like athletic tape, braces, and orthotics provide added stability to healing joints and muscles.

- Taping techniques can offload stress from injured areas such as the shoulder, wrist, or knee, allowing the diver to train with reduced pain and risk.

- Braces offer firmer support in cases of ligament damage or instability.

- Custom orthotics can correct foot posture and alignment to prevent further stress up the kinetic chain.

These tools should be used alongside active rehabilitation and under the guidance of a medical professional.

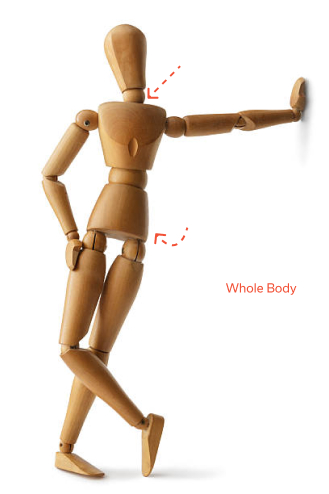

Physiotherapy

Physiotherapy plays a central role in the recovery process. A trained physiotherapist can assess movement deficits, identify weaknesses, and guide the diver through a progressive rehabilitation plan. This includes:

- Strengthening exercises

- Flexibility work

- Joint mobilisation

- Neuromuscular training

- Return-to-dive conditioning

Physiotherapy also helps address asymmetries and prevent compensatory movement patterns that could lead to future injuries. Ongoing assessment and communication with coaches ensure the diver’s reintegration into training is smooth.

Competitive Diving Injuries – Prevention

Prevention is an integral part of competitive diving training, as the sport’s repetitive and high-impact nature makes divers vulnerable to overuse and acute injuries. Injury prevention enables consistent performance, builds resilience, and supports long-term athletic development. A structured programme focused on physical preparation, technical execution, and injury-specific exercises can dramatically reduce the likelihood of setbacks.

Proper Preparation

- Warm-up before training or competition.

- A comprehensive warm-up activates muscles, lubricates joints, and primes the nervous system for explosive movement.

- Skipping this step increases the risk of strain and poor coordination during dives.

- Strengthen supporting muscle groups.

- Divers should focus on core strength, glute activation, shoulder stabilisers, and ankle mobility.

- These areas help maintain proper alignment, absorb force during entry, and reduce pressure on joints.

Proper Technique

- Coaches should ensure safe and correct form during take-offs, flips, and entries.

- Flawed mechanics not only limit performance but also increase mechanical stress on joints and soft tissues.

- Avoid overtraining.

- Repetitive stress without adequate rest leads to fatigue, form breakdown, and higher injury risk.

- Periodised training plans and rest days are essential, especially during competition prep or growth spurts in young athletes.

Preventive Exercises

- Focus on joint mobility, core strength, and balance.

- These qualities are foundational to stable, controlled movement.

- Balance training also reduces fall risk on wet platforms and during mid-air transitions.

- Address muscle imbalances early to reduce the risk of injury.

- Regular screening and corrective programmes help detect tightness, weakness, or asymmetry before they become problematic.

- Prevention, in this context, is a year-round priority, not just something done during rehab.

Conclusion

Diving is thrilling, but it’s not without risks. Injuries can happen to even skilled divers. However, the good news is that most of the injuries mentioned here are preventable. The key is preparation: knowing your body, your limits, and the risks involved. Understand the common injuries, respect the warning signs, and dive with intention. When you train smart and stay aware, you protect not just your performance but your future in the sport.

Browse other articles by category

Physiotherapy for Knee Pain Physiotherapy For Slipped Disc Physiotherapy for Neck Pain PHYSIOTHERAPY

PHYSIOTHERAPY

Hand Therapy

Hand Therapy

Alternative

Alternative

Massage

Massage

Traditional Chinese Medicine Treatment

Traditional Chinese Medicine Treatment

Rehab

Rehab

Physiotherapy For Lower Back Pain

Physiotherapy For Shoulder Pain

Orthopedic Doctors, Insurance & Healthcare

Physiotherapy For Upper Back Pain

Frozen Shoulder

Physiotherapy for Back Pain

Physiotherapy For Lower Back Pain

Physiotherapy For Shoulder Pain

Orthopedic Doctors, Insurance & Healthcare

Physiotherapy For Upper Back Pain

Frozen Shoulder

Physiotherapy for Back Pain

Whatsapp us now

Whatsapp us now